Keywords: Reverse radial forearm flap, Burn wound management, Hand surgery

Authors: David Salim, MD and Taiba Alrasheed, MD, FRCSC, Msc. Institution: Department of Plastic- & Breast Surgery, Zealand University Hospital Roskilde, Denmark

Abstract

A 55-year-old man had sought and was admitted to the emergency department one week after sustaining a superficial second degree burn wound on the hypothenar region of the right hand after accidentally placing it on a hot stove. At first sight, the burn wound seemed quite superficial and conservative healing and bandaging was initially deemed sufficient with the aim of spontaneous healing. One week after the initial assessment in the emergency department, the patient was seen for a routine clinical control of the wound. At this consultation, the patient scored 4/4 positive Kanavel’s signs and flexor tenosynovitis was suspected. Afterwards immediate wound revision of the right hypothenar was conducted. During wound revision, considerable amounts pus was noted and furthermore the musculus abductor digiti minimi was avital and excised. Suitable wound dressing was applied, pus was sent for culture and sensitivity testing and the patient was gives appropriate peroral antibiotics. After numerous wound revisions and debridement, control of the infection at the orthopedic surgery department was achieved. The patient was then referred to the plastic surgery department for planning of soft tissue coverage with a reverse radial forearm flap.

Patient medical history

The patient was known to have substantial unregulated diabetes mellitus type two, but no other known medical comorbidities.

Before and After

Patient examination

The patient was seen in an outpatient setting in the plastic surgery department for planning of surgery. The defect was located to the whole hypothenar region of the right hand. Substantial soft tissue loss was noted and the 3-5th flexor tendons were exposed.

Pre-operative considerations

One week after sustaining the burn wound of the right hypothenar.

One week after the patient had sustained the burn wound of the right hypothenar region. At first sight, it does not look very affected and only seems to be damaged by the burn accident in the epidermis and superficial dermis.

Two weeks after sustaining the burn wound of the right hypothenar.

Beginning ulceration of the skin and pyogenic infection.

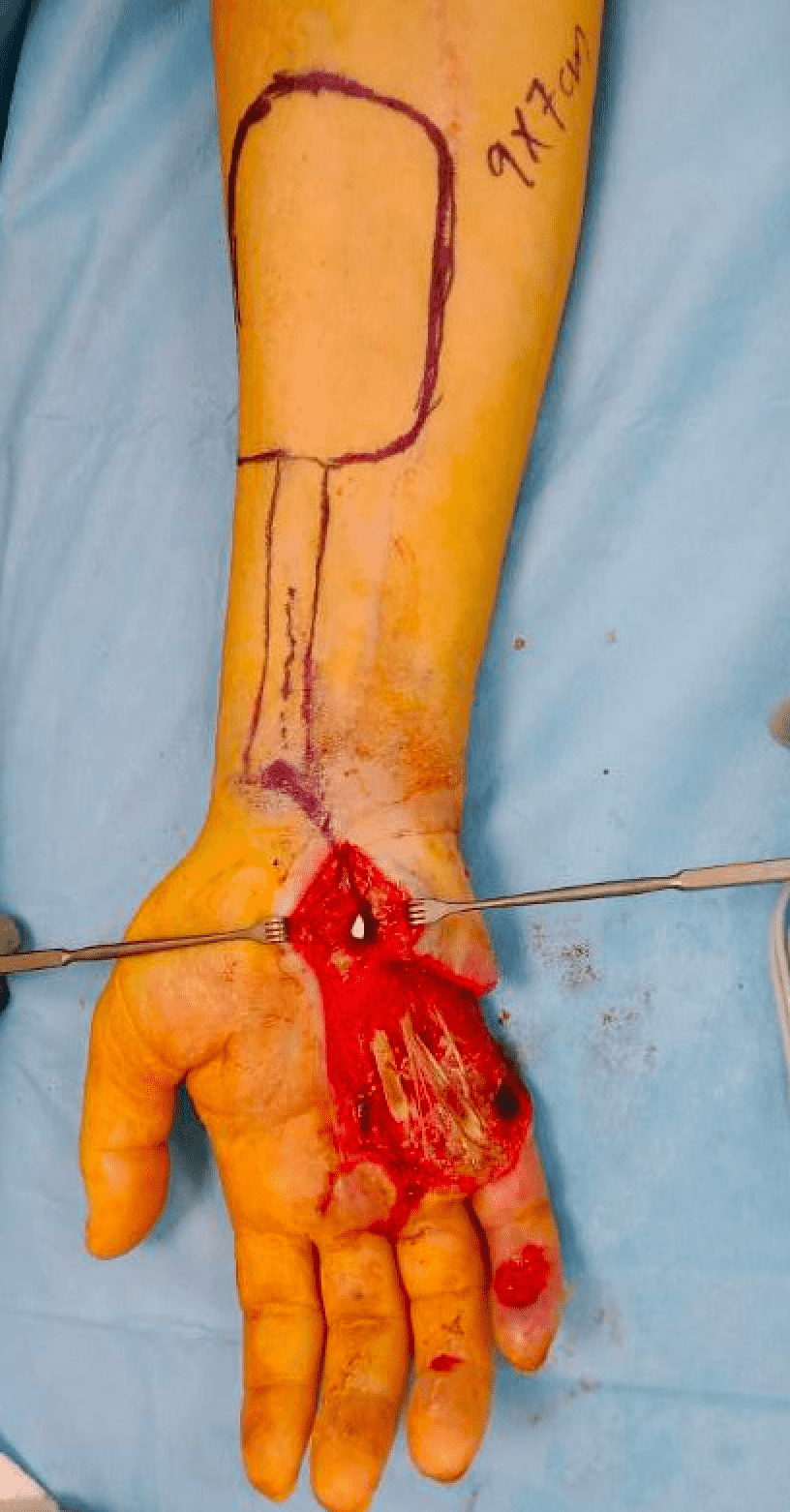

Preoperative markings for the reverse radial forearm flap

Preoperative markings for a RRFF are crucial for ensuring safe flap harvest, adequate vascular supply, and optimal functional outcomes. The first step is to identify and mark the course of the radial artery, which is best done using a handheld Doppler. The artery runs along the forearm between the flexor carpi radialis (FCR) and brachioradialis (BR) muscles, extending from the wrist proximally toward the antecubital fossa. This marking is essential to guide dissection and avoid accidental injury to the vascular supply.

The pedicle pivot point must be marked approximately 1–2 cm proximal to the radial styloid, ensuring that the flap has sufficient length to reach the hypothenar defect without excessive tension. It is important to passively move the wrist into flexion and extension to confirm that the flap will mobilize properly to the defect site without excessive restriction.

Next, the flap dimensions are outlined based on the size of the defect, in this case, the hypothenar region. The proximal boundary of the flap should be just distal to the antecubital fossa, allowing for an adequate vascular pedicle length, while the distal boundary extends to the wrist, ensuring the preservation of the palmar arch for retrograde perfusion. The width of the flap should generally remain within 8–10 cm to allow for primary closure when possible, or minimal use of a skin graft if necessary. The center of the flap should be positioned directly over the radial artery to ensure optimal perfusion.

Raising the flap

Once markings are complete, the tourniquet is inflated to create a bloodless field. Incisions are made along the flap borders, beginning at the ulnar side and extending distally to the wrist. Dissection proceeds in the subfascial plane, preserving the radial artery, its venae comitantes, and the cephalic vein within the flap. The radial sensory nerve is carefully identified and protected to prevent postoperative sensory deficits. As the flap is elevated, perforating branches from the radial artery to the flexor tendons and muscle bellies are ligated to free the vascular pedicle. The cephalic vein, which plays a crucial role in venous drainage, is included within the flap to prevent venous congestion. The proximal radial artery is identified and ligated just distal to the antecubital fossa, ensuring that blood supply is maintained through retrograde perfusion via the palmar arch.

Flap inset and skin grafting of the donor site

Once fully elevated, the flap is carefully mobilized toward the defect, ensuring there is no excessive tension. The distal pivot point, located approximately 1–2 cm proximal to the radial styloid, is assessed to confirm that the flap can reach the recipient site without restriction. If necessary, subcutaneous or fascial release is performed to facilitate movement. The flap is then inset into the defect using meticulous suturing techniques, ensuring tension-free closure. The donor site is assessed for closure, and if primary closure is not possible, a split-thickness skin graft is harvested as in this case, typically from the thigh, and applied. Finally, the tourniquet is deflated, and flap perfusion is reassessed. Postoperatively, the limb is immobilized in a splint, and close monitoring is performed to ensure flap viability, with early intervention for any signs of ischemia or congestion.

Side view after flap inset

The flap is inset into the defect using meticulous suturing techniques, ensuring tension-free closure. If venous congestion is noted, adjustments may be made, including optimizing cephalic vein outflow or using a microvascular anastomosis if required.

Two months after surgery

Functional flap and complete healing of the donor site with a STSG. Only a minor defect of about 10×15 mm on the fifth digit distally remained, which was planned to heal conservatively.

Pearls

The reverse radial forearm flap has excellent arc of rotation and reach and is a workhorse in reconstruction of considerable soft tissue defects in the palm, hypothenar, thenar, digits, and even dorsal hand.

It can be utilized either as a pedicled flap without microsurgical anastomosis or a free flap.

It is a thin, pliable flap with minimal bulk and provides vascularized, flexible coverage for tendons, nerves, and joints without restricting movement.

Pitfalls

The retrograde venous drainage can be unreliable, increasing the risk of flap congestion and failure, especially in patients with poor venous outflow.

Post-operative plan

The patient was hospitalized seven days after the surgery in the ward.

Immediate Postoperative Care (the first 24 hours after surgery)

Early Postoperative Period (1–7 Days)

Intermediate Recovery (1–4 Weeks)

Gradual hand rehabilitation began with passive range of motion exercises after 7–10 days, progressing to active range of motion after 3–4 weeks. Wound healing monitoring was done during routine clinical control appointments in a out-patient setting to assess for infection and wound dehiscence while also assessing status of the flap.

Long-Term Recovery (1–3 Months and Beyond)

References

- 1) Maan ZN, Legrand A, Long C, Chang JC. Reverse Radial Forearm Flap. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017 Apr 3;5(4):e1287. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001287. PMID: 28507856; PMCID: PMC5426875.

- 2) Hansen AJ, Duncan SF, Smith AA, Shin AY, Moran SL, Bishop AT. Reverse radial forearm fascial flap with radial artery preservation. Hand (N Y). 2007 Sep;2(3):159-63. doi: 10.1007/s11552-007-9041-7. Epub 2007 May 2. PMID: 18780079; PMCID: PMC2527146.

- 3) Hwang K, Son JS, Ryu WK. Smoking and Flap Survival. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2018 Nov;26(4):280-285. doi: 10.1177/2292550317749509. Epub 2018 Jan 9. PMID: 30450347; PMCID: PMC6236508.

- 4) Dasari N, Jiang A, Skochdopole A, Chung J, Reece EM, Vorstenbosch J, Winocour S. Updates in Diabetic Wound Healing, Inflammation, and Scarring. Semin Plast Surg. 2021 Aug;35(3):153-158. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1731460. Epub 2021 Jul 15. PMID: 34526862; PMCID: PMC8432997.